In the dusty hills of Burkina Faso, young men with calloused hands dig through the earth in search of gold. Their tools are basic – shovels, pickaxes, and sometimes even their bare hands. Many of them are boys, barely teenagers. They dig from sunrise to sundown, hoping to strike just enough gold to feed their families.

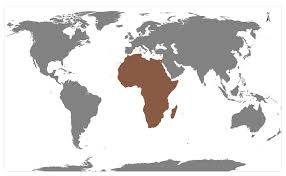

Across Africa, from the Democratic Republic of Congo to Ghana and Sudan, scenes like this are common. Informal, or “artisanal,” mining has become both a lifeline and a curse. While it offers a way out of deep poverty for millions, it also traps them in dangerous conditions, exploitation, and violence.

Gold and Dreams

Africa is rich in natural resources. Gold, diamonds, cobalt, and other minerals lie beneath its soil. But in many regions, formal mining operations are limited, and government oversight is weak. As a result, informal mining has flourished.

In Ghana, informal miners are known as “galamsey” workers – a term born from the phrase “gather them and sell.” These miners often operate illegally, digging without permits and sometimes inside restricted areas. In Mali, entire villages revolve around hand-dug pits. Children skip school to help their parents in the mines, inhaling dust and chemicals like mercury.

“It’s our only option,” says Aboubacar, 17, who started mining when he was 12. “There’s no work, no school, no future – only gold.”

The Price of Gold

But the gold doesn’t stay in Africa. Once extracted, it’s sold to middlemen and quickly disappears into global supply chains. Some ends up in luxury jewellery stores. Others are used in electronics – smartphones, laptops, even medical devices. Most consumers have no idea that their gold may have been mined by a child in dangerous conditions.

And the human cost is heavy.

In eastern Congo, the search for valuable minerals like coltan and gold has fuelled decades of conflict. Armed groups control mines and force civilians to work under brutal conditions. Rape, murder, and forced labour are common. In Sudan, informal mining regions have become hotspots for human trafficking and ethnic violence.

“We call it ‘blood gold’,” says Mariam, a rights activist based in Khartoum. “The world profits, but we bleed.”

Poisoned Lands and Bodies

The environment pays a price too. Informal miners often use mercury to separate gold from rock. Mercury is toxic – it poisons rivers, soil, and the people who use it. In some mining towns, children are born with birth defects. Livestock die. Crops fail.

“We used to farm,” says Joseph, a farmer turned miner in northern Nigeria. “Now the land is dead. And we are dying too.”

In some cases, collapsed tunnels bury miners alive. Without proper safety equipment or medical care, injuries and deaths are common – and often unreported.

A Way Forward?

Efforts to regulate and support artisanal mining have had mixed results. Some governments have tried to legalise small-scale mining, offering training and safer tools. But corruption, weak enforcement, and poverty continue to drive miners into dangerous, illegal operations.

NGOs and human rights groups are calling for greater transparency in supply chains and more responsibility from global corporations.

“Big companies must know where their gold comes from,” says Elodie, a researcher with an international watchdog group. “They must invest in safe, fair mining – or stop buying from sources that exploit workers.”

For now, the miners keep digging. With every shovelful of earth, they hope for a better life – one where gold doesn’t come at the price of blood.

Note: Names have been changed to protect identities.