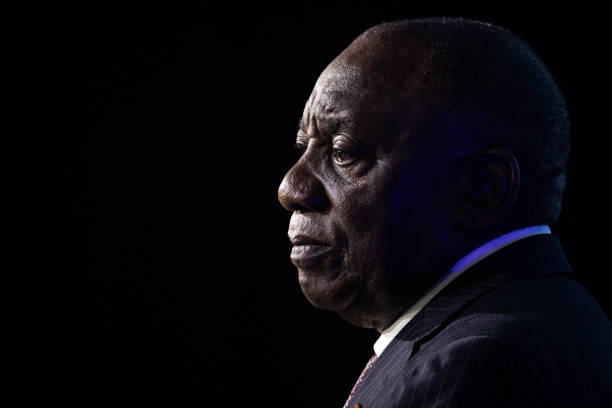

When Cyril Ramaphosa took the oath of office as South Africa’s president in 2018, the country breathed a cautious sigh of relief. After nearly a decade of Jacob Zuma’s scandal-plagued leadership, many believed Ramaphosa would be the man to clean house — a principled leader with the pedigree to restore faith in government and rebuild a struggling economy.

Here was a man who had walked the long road with Nelson Mandela, negotiated the end of apartheid, and earned his stripes as a trade unionist with fire in his belly. Yet, paradoxically, here too was a billionaire businessman, with boardroom ties and a hefty personal fortune.

Ramaphosa’s rise from mineworker representative to corporate giant is as remarkable as it is complicated. He made his early mark leading the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), helping organise massive strikes against apartheid’s exploitative labour system. But after democracy dawned, he took a surprising detour — away from Parliament and into business, amassing a vast fortune through black economic empowerment deals.

For some, this was proof of his shrewdness. For others, a betrayal. How could a man of the people live behind high walls, surrounded by wealth, while inequality deepened on the outside?

The Hope He Carried

When the ANC recalled Jacob Zuma and handed the baton to Ramaphosa, he was seen as the anti-Zuma. Calm where Zuma was chaotic, measured where Zuma was brazen. His campaign to cleanse the state of corruption — dubbed the “New Dawn” — was met with cheers from weary citizens and cautious optimism from investors.

“He understands the economy,” people would say. “He knows how business works.” For a while, even the markets seemed to believe it.

But nearly seven years later, many are asking: where is the dawn?

Promises vs Performance

On paper, Ramaphosa’s presidency has seen some wins. The Zondo Commission, set up to probe state capture under Zuma, exposed deep-rooted corruption and gave the country a clear picture of just how badly institutions were abused. Several reforms followed — at the revenue service, state-owned enterprises, and in public procurement systems.

Yet, for the ordinary South African, life has not improved.

Load-shedding continues to darken homes and businesses. Unemployment remains sky-high. Crime is rampant. Trust in government is scraping the bottom.

Ramaphosa’s measured, consensus-driven leadership — once praised as diplomatic — is now criticised as indecisive. His party, the ANC, appears more fractured than ever. Even within his cabinet, loyalty is divided.

And then came Phala Phala.

The 2020 scandal involving foreign currency hidden in a couch at Ramaphosa’s game farm was the final straw for some. Though he denied wrongdoing and survived an impeachment threat, the damage was done. The man who had promised clean governance now appeared tarnished himself.

The Contradiction at the Core

Ramaphosa remains a study in contrasts. He speaks the language of the poor, yet lives in the world of the rich. He champions democracy, yet leads a party accused of eroding it. He fights corruption, yet struggles to hold allies accountable.

Perhaps the biggest contradiction is the burden of expectation. South Africans projected their hopes onto Ramaphosa — not just to be better than Zuma, but to be what Mandela might have been in modern times. That weight was always going to be too heavy for one man.

As the country heads into a new political chapter, with the ANC having lost its majority for the first time, Ramaphosa faces an even tougher road. He now leads a government of national unity — a coalition of strange bedfellows — in an era of growing political uncertainty.

Still Standing, But For How Long?

At 72, Cyril Ramaphosa remains composed, soft-spoken, and strategic. But the patience of the nation is wearing thin. Critics say his presidency has lacked urgency. Supporters argue he inherited a broken system and needed time to fix it.

Time, though, is running out.

The billionaire democrat is still in power — but his legacy hangs in the balance. Whether history remembers him as the man who steadied a sinking ship, or simply rearranged the chairs on its deck, remains to be seen.

One thing is clear: Ramaphosa may have been the right man for the ANC, but was he the right man for South Africa? That question is still waiting for an answer.